Note: This article is motivated by our experience working with Prefect community members deploying their Prefect workflows, but Prefect knowledge is not required to go through it.

Photo by Guillaume Bolduc on Unsplash

Outline

- Motivation

- Making a Python package

- Writing a Dockerfile

- Building and Using the Image

Motivation

Data scientists and analysts often shy away from packaging their Python work into Docker containers for production. From our experience in supporting the Prefect community, a lot of data professionals have the mistaken impression that Python packaging and building a Docker container is too hard a task for them to attempt. Oftentimes it boils down to taking the first step and they don’t know where to start. In this walkthrough, we’ll provide an end-to-end minimal example of how to do it.

It is widely known that using a container provides an isolated environment to run workflows consistently, but there are other practical benefits gained by using containers.

- Portability — services such as AWS ECS can take a Docker container and run a batch job. This eliminates the need to have compute resources consistently turned on as workloads can be deployed by a smaller, lightweight machine. Tools such as Kubernetes also use containers as the unit of orchestration.

- Scalability — distributed compute frameworks such as Dask require clusters to have the same modules installed across the scheduler and workers. Docker images are normally provided during the cluster spin-up so that tasks can be run with the same behavior across machines.

- Reliability — it is very common for Dask workers or Kubernetes pods to die. Having the Docker image allows these processes to be spun up again with the same configuration. These services can also do it automatically for users.

Making a Python Package

We’ll start by making a Python package. But before that, we’ll show what the final directory structure will look like below. These files and directories will be described one-by-one. We’ll start with the components and workflow folders, and then go into the requirements.txt, setup.py, and the Dockerfile.

All of the code can be found here so there’s no need to create these files yourself.

mypackage/

├── components/

│ ├── init.py

│ ├── componentA.py

│ ├── componentB.py

├── workflow/

│ ├── flow.py

├── requirements.txt

├── Dockerfile

└── setup.py

Components

The most common use case that Prefect community members encounter is wanting to port over a set of common utilities and functions to their execution environment. The components folder in the directory structure above represents these common functions needed by our application.

If you find that components are being reused across multiple projects, it might be worth abstracting them out into their own package. Moreover, putting common logic into a package allows it to be imported regardless of the present working directory, which makes life easier when running within a Docker container.

Here we define some quick classes in our component files. This is just simple Python. The goal is to create something that we can import within our main Python script.

ComponentA.py

class ComponentA:

def init(self, n=2) -> None:

self.n = n

ComponentB.py

class ComponentB:

def init(self, n=2) -> None:

self.n = n

init.py

This file will just be empty. The presence of this file tells Python that this directory represents a submodule. For example, mypy and pytest require empty init.py files to interpret the code structure. For more information, see this StackOverflow post.

Workflow

This folder in the directory structure above will hold our main application. The code for flow.py can be seen below. In it, we have a basic Prefect Flow, but you don’t need to know Prefect here (but we’ll explain a bit). The main point is that we imported ComponentA and ComponentB, and used it in a Python script.

flow.py

For those that are curious, Prefect is a workflow orchestration system that schedules and monitors workflows. Prefect flows represent the entire end-to-end logic (like Python scripts), while tasks, defined with the @task decorator, represent the individual components of a workflow (like functions).

Prefect is general-purpose and is capable of running flows that range from ETL to Machine Learning jobs. Anything that can be written in Python can be orchestrated with Prefect. Once deployed, our flow above will use the test:latest image when run (as specified in the configuration of **DockerRun**).

Requirements

The requirements.txt file should be familiar to most users. It holds all of the Python requirements you need to run the code. Ideally, requirements should be versioned, otherwise, you can get upgraded versions the next time you install them. For this workflow, we only have one requirement.

requirements.txt

prefect==0.15.4

You can create this file for your project with the following command, which will output all of your packages into the requirements.txt file.

pip freeze > requirements.txt

The setup.py File

Everything so far is probably not new. We created some Python classes, imported them into the flow.py file, and then created our requirements. The setup.py is what might be new for some users. This file will tell pip how to install our package.

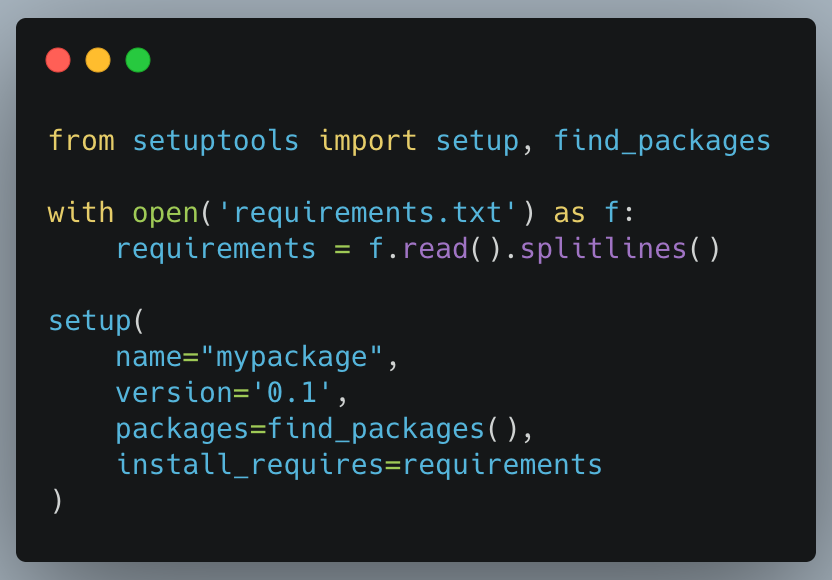

setup.py

With this file, we can now install our package locally with pip install -e . . Our setup.py here is pretty minimal. The package name and version are used by pip to keep track of the package, but they don’t affect how the package is used in Python code. The find_packages function call goes through the subdirectories with an init.py and includes them in mypackage. Note that workflow/flow.py will not be included in the library because there is no init.py in the workflow folder.

The -e in pip install -e .tells pip to install the library in development mode, so that edits to the code can take effect without re-installing.

The requirements.txt file is read in and then passed to the setup function. This tells pip to install those dependencies along with our package. With that, we now have a Python library that we can install on other machines as long as we copy the code over.

Writing a Dockerfile

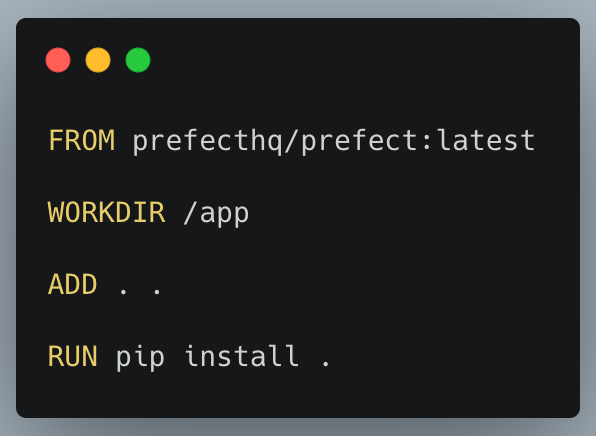

This is the last part of our codebase. The goal is to copy over our Python package that we just created and installed. We’ll show the code and then go over it line by line.

Dockerfile

- FROM — this is the base image that we’ll be using for our image. Projects such as Spark or Dask. These are especially useful when you are using tools that are not confined to Python. For example, Spark needs Java in the container also, and using the base Spark image takes are of that.

- WORKDIR — set the working directory for the container. It will be created if it doesn’t exist

- ADD — here we add all of our files from the current directory to the container WORKDIR

- RUN — this is where we install our library (-e is not really needed as that’s for development). This will also install all requirements because of the way we structured our setup.py file earlier.

Building an Image

With the Dockerfile created, we can create the image from the root of the project. This can be done with the following command in the CLI. Note that this assumes you have Docker installed and it’s running.

docker build . -t test:latest

Now that the image has been created, you can push it to your registry (Dockerhub, AWS ECR, etc.) using the docker push command. These registries will have different ways to do it so we won’t cover it here.

Using the image

In order to run the image interactively,

docker run –name mycontainername -i -t test:latest sh

and from here, you should be in the app directory and you can run:

python workflow/flow.py

Conclusion

In this walkthrough, we have gone through how to create a Python package by including the requirements.txt and setup.py files. We were then able to copy it over into a Docker image and install it for general use.

Having the image working on a local machine provides some benefits already, but the image will likely be needed to be uploaded to a registry for production use cases.