Written by Kevin Kho and Han Wang

This is a written version of our most recent PyCon talk.

Photo by Jukan Tateisi on Unsplash

Pandas-like Frameworks for Distributed Computing

Over the last year and a half, we’ve talked to data practitioners who want to move Pandas code to either Dask or Spark to take advantage of distributed computing resources. Their workloads were quickly becoming too compute-intense or their datasets would not fit in Pandas anymore, which only runs on a single machine.

One of the recurring themes in our conversations was tools like Koalas (renamed to PySpark Pandas) and Modin that aim to use the same Pandas interface to bring workloads to Dask, Ray, or Spark just by changing the import statement (for the most part).

For example, the PySpark Pandas drop-in replacement would be:

python1# import pandas as pd

2import pyspark.pandas as pd

and supposedly, everything should run on Spark. There are already some blogs that show this isn’t entirely true (as of May 2022). There are some hiccups here and there, but we’re not here to talk about slight discrepancies. This post is about fundamental differences that will always exist because of the nuances of distributed computing that Pandas isn’t compatible with.

Pandas-like frameworks are popular because a lot of data scientists are resistant to change (I’ve been there myself!). But just changing the import statement allows users to avoid understanding what is really happening in the distributed system and the lack of understanding leads to ineffective usage.

We’ll see that the attempt to achieve 1:1 parity with the Pandas API will require compromises on performance and functionality.

Data for Benchmarking

We created a DataFrame with the following structure. Columns a and b are string columns. Columns c and d are numerical values. This DataFrame will have 1 million rows (but we will also change it in some cases).

We will create this DataFrame in Pandas, Modin (on Ray), PySpark Pandas, and Dask. For each backend, we will time the operations of different cases. This should be clearer after the first issue is discussed.

Issue 1: Pandas Assumes Data is Physically Together

One of the most used Pandas methods is iloc . This relies on an implicit global ordering of data. This is why Pandas can quickly retrieve the rows in a given set of index values. It knows where to access the memory of the row it needs to retrieve.

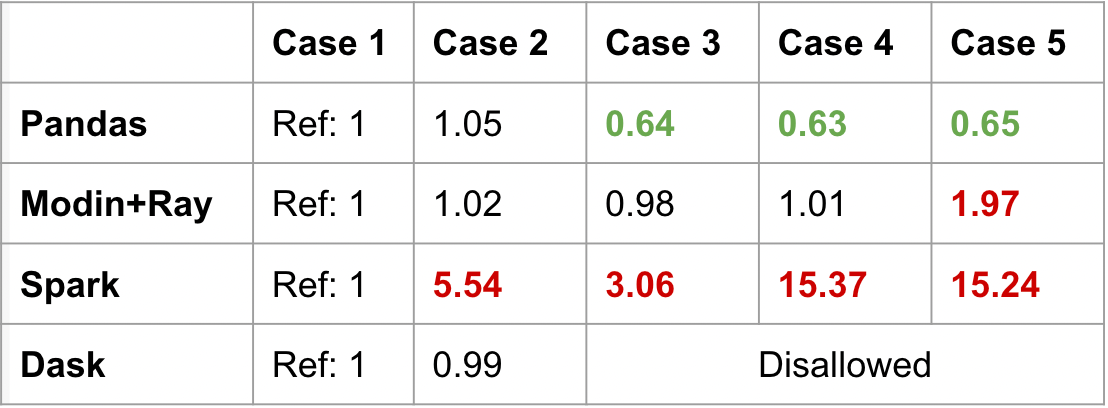

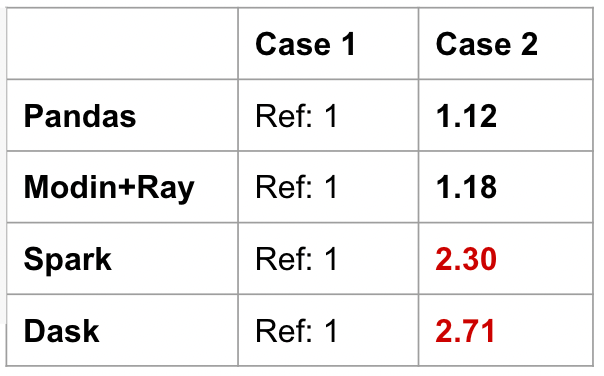

Take the following 5 cases in the code snippet below, we’ll evaluate the speed of each operation relative to Case 1. We do not compare across frameworks. We want to see the different performance profiles of each framework. Cases 3–5 below are accessing rows and columns based on location. Case 5 specifically is the middle of the DataFrame. We will run these five cases on Pandas, Modin, PySpark Pandas (also known as Koalas), and Dask.

python 1# case 1

2df.head(10)[["c","d"]]

3

4# case 2

5df.tail(10)[["c","d"]]

6

7# case 3

8df.iloc[:10, [2,3]]

9

10# case 4

11df.iloc[-10:, [2,3]]

12

13# case 5

14df.iloc[499995:500005, [2,3]]

In the benchmark below, Pandas speeds up when using integer-position values to access the data. This is because it’s relatively cheap to access in-memory data on a single machine. Modin does a great job of giving a consistent performance across the cases, but there is a 2x slow down when accessing the middle of the DataFrame (case 5).

PySpark Pandas (labeled as Spark in the table) and Dask give interesting results. Spark has significant slowdowns across all cases. Getting the head is relatively optimized, but everything else is less performant. In fact, getting the tail or the middle of the DataFrame result in 15x the duration of getting the head (case 1).

Dask actually disallowed using iloc on rows. In order for iloc to behave the same way as Pandas, there must be compromises to performance to maintain that global ordering. This was an intentional design decision to deviate from the Pandas semantics to maintain performance.

PySpark Pandas prioritizes maintaining Pandas parity, at the cost of performance. Meanwhile, Dask is more sensitive to preventing bad practices. Contrasting these frameworks shows us the difference in design philosophies. This is also the first indication that a unified interface does not mean a consistent performance profile.

Issue 2: Pandas Assumes Data Shuffle Is Cheap

In a distributed setting, data lives on multiple machines. Sometimes, data needs to be rearranged across machines so that each worker has all the data belonging to a logical group. This movement of data is called a shuffle and is an inevitable, but expensive part of working with distributed computing.

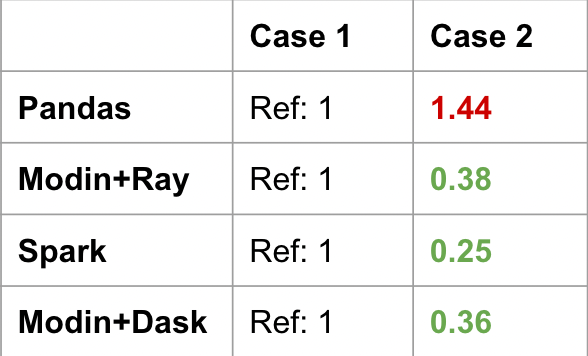

Take the two equivalent operations. The goal is to keep the row with the highest value of c for each value of d. Note a groupby-max does not preserve the whole row. Case 1 performs a global sort and then drops duplicates to keep the last row. Case 2 on the other hand uses a groupby-idxmax operation to keep the maximum row. Then the smaller DataFrame is merged back to the original DataFrame. This benchmark used 100k rows instead of 1 million.

python1# case 1: more shuffle

2df.sort_values(["c","d"]).drop_duplicates(subset=["d"], keep="last")

3

4# case 2: less shuffle

5idx = df.groupby("d")["c"].idxmax()

6df.merge(idx, left_index=True, right_on="c")

For Pandas, Case 2 is actually slower than Case 1 as seen in the table below. All of the distributed computing frameworks are significantly faster with Case 2 because they avoid the global sort. Instead, the groupby-idxmaxis an optimized operation that happens on each worker machine first, and the join will happen on a smaller DataFrame. The join between a small and large DataFrame can be optimized (for example, broadcast join).

This is an example of a very common Pandas code snippet that doesn’t translate as well to the distributed setting. Similar to the global ordering discussion in Issue 1, doing a global sort is a very expensive operation.

The problem with Pandas-like frameworks is that users end up approaching big data problems with the same local computing mindset. It’s very easy to run into sub-optimal operations that take way longer than they should if users don’t change code when migrating to distributed settings.

Issue 3: Pandas Assumes the Index is Beneficial

One of the core concepts ingrained in the Pandas mindset is the index. If a user comes from a Pandas background, they assume that the index is beneficial and it’s worth setting or resetting it. Let’s see how this translates to other backends.

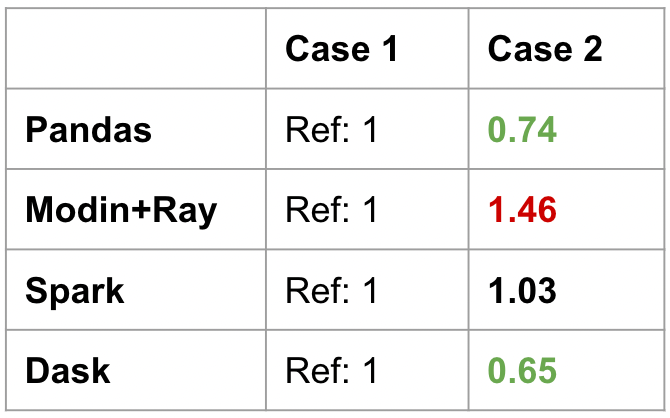

Take the code snippet below. We filter for a given group and then calculate the sum of those records. Case 1 has no index, and case 2 uses an index.

# case 1: without index

df[df["a"]=="red"]["c"].sum()

# case 2: with "a" as index

idf = df.set_index("a")

idf.loc["red"]["c"].sum()To be specific, the set_index was not included in the benchmark. This is because set_index has its own overhead. The results can be seen below:

For Pandas, there is a speed up when the DataFrame is indexed by a . For Modin or Spark, there is no improvement. Dask has a significant improvement.

Again, a unified interface does not mean a consistent performance profile. Often, user expectations will not be met for certain operations. There is no way to have a good intuition for this either. We already know that compromises have to be made to support a distributed version of the Pandas API, but it’s hard to know what exactly those design decisions were. Each of the Pandas-like frameworks requires specific optimizations in different directions.

Note also that for all of the Pandas-like frameworks mentioned above, MultiIndex is not fully supported.

Issue 4: Eager versus Lazy Evaluation (Part One)

Lazy evaluation is a key feature of distributed computing frameworks. When calling operations on a DataFrame, a computation graph is constructed. The operations only happen when an action is performed that needs the data.

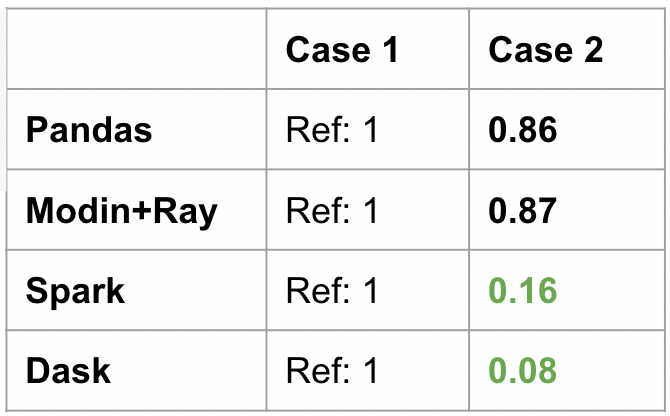

In the code snippet below, Case 1 reads the file and calculates the min of all columns. Case 2 reads the file and calculates the min of two columns. For this issue, we will use a different dataset. This new one has 40 columns and 2 million rows of random numbers. There are two or three steps in this one-line expression: loading the file, filtering the columns, and then getting the minimum.

python1# case 1: read file and min of all columns

2backend.read_parquet(path).min()

3

4# case 2: read file and min of two columns

5backend.read_parquet(path)[["c0","c1"]].min()

The results are seen below. Because Pandas and Modin evaluate things eagerly, Case 2 is just a slight reduction from Case 1. This is because there is less computation happening for the minimums (two columns instead all). But the speedup is not that much because the whole data is read first before filtering the needed columns.

On the other hand, PySpark Pandas and Dask have tremendous speedups for this operation. This is because they are aware only two columns are needed in the end, so they only load those two columns from the parquet (one benefit of parquet over csv files). For the three operations (load, filter, min), PySpark Pandas and Dask were able to optimize the computation by minimizing disc I/O due to their lazy nature.

Modin specifically chose to optimize the experience of iterative workloads, and also match the Pandas behavior. On the other hand, PySpark Pandas chose to have the same lazy evaluation as Spark. Even if both of them are a form of “distributed Pandas”, they have very different performance profiles.

Issue 4: Eager versus Lazy Evaluation (Part Two)

Here, we see a case where eager evaluation helps users. But when practitioners don’t understand lazy evaluation, it also becomes very easy to run into duplicated work.

See the following cases, Case 1 just gets the min of two columns while Case 2 gets the min, max, and mean.

python1# case 1: min of 2 columns

2sub = backend.read_parquet(path)[["c0","c1"]]

3sub.min()

4

5# case 2: min, max, and mean of 2 columns

6sub = backend.read_parquet(path)[["c0","c1"]]

7sub.min()

8sub.max()

9sub.mean()

In the results below, Pandas and Modin don’t seem to have any recomputation happening in case 2. sub is already held in memory after being read. This is expected because of what we saw in the last benchmark where Pandas and Modin evaluate eagerly. On the other hand, PySpark Pandas and Dask show that sub is being computed multiple times because we did not explicitly persist sub .

In Issue 4 we saw both sides of lazy evaluation. We saw one scenario where it led to drastic speedups, and in this last scenario, we saw it cause slowdowns when used improperly. This doesn’t mean that either eager or lazy evaluation is better, the more important takeaway is that we need to be mindful of what the framework is doing as we work on big data to get the best results.

This is a common pitfall because the Pandas doesn’t have the grammar to make users mindful of this intricacy of distributed computing. People coming from Pandas are not aware of the persist operation.

Conclusion

Pandas is great for local computing (aside from the fact there are too many ways to do some operations). But we need to recognize the inherent limitations of the interface and understand it was not built to scale over several machines. Pandas was not designed to be an interface for distributed computing.

If you want to try another semantic layer that is not Pandas-like, Fugue takes a different approach. Fugue is an open-source abstraction layer for distributed computing. While it can bring Pandas code to Spark and Dask, it intentionally decouples from the Pandas interface to avoid facing the compromises Pandas-like frameworks had.